Subscribe to my newsletter, The Wavelength, if you want the content on my blog delivered to your inbox four times a week before it’s posted here. The Wavelength will transition to a subscription product early in 2022. Details to come.

In the last issue, we looked at the €225 million punishment for WhatsApp levied by the Data Protection Commission for failing to meet the General Data Protection Regulation’s (GDPR) requirements on transparency in its data processing (see here for more detail and analysis.) Today, let’s look at the European Data Protection Board’s (EDPB) binding decision that directed DPC to revise and stiffen its proposed punishment of WhatsApp, which is more extensive than just a fine, for the company has a significant list of items on which it must act or face future regulatory action. But first, a little background.

The DPC started investigating WhatsApp in December 2018 after complaints from people using WhatsApp and people not using the messaging app. The DPC received 88 complaints from other DPAs, some of which ultimately objected to the DPC’s draft decision. Per the GDPR, the DPC circulated its draft decision in December 2020, and after assessing the objections it received from the other DPAs (aka supervisory authorities (SA)) and considering further WhatsApp input, the DPC issued a compromise decision. However, this compromise satisfied some of the DPAs but not others, and finally in May 2021, the DPC referred the decision to the EDPB for resolution.

In late July 2021, the EDPB announced its adoption of an Article 65 dispute resolution decision that “seeks to address the lack of consensus on certain aspects of a draft decision issued by the Irish (IE) SA as LSA regarding WhatsApp Ireland Ltd. (WhatsApp IE) and the subsequent objections expressed by a number of concerned supervisory authorities (CSAs).” But, at the time, this press release was the only public information offered about the decision that has now been released. The EDPB has already issued one Article 65 decision in regard to the DPC that functionally overruled the agency and revised upward its proposed punishment of Twitter for data breaches. In a recent related development, the EDPB also turned down the Hamburg DPA’s request for an urgent binding order on WhatsApp and Facebook’s new privacy and policy and terms of service (see here for more detail and analysis). The EDPB did urge the DPC to investigate, which appears to overlap with this Article 65 proceeding. In the press release, the EDPB further explained:

- The LSA issued the draft decision following an own-volition inquiry into WhatsApp IE, concerning whether WhatsApp IE complied with its transparency obligations pursuant to Art. 12, 13 & 14 GDPR. On 24 December 2020, the LSA shared its draft decision with the CSAs in accordance with Art. 60 (3) GDPR.

- The CSAs issued objections pursuant to Art. 60 (4) GDPR concerning, among others, the identified infringements of the GDPR, whether specific data at stake were to be considered personal data and the consequences thereof, and the appropriateness of the envisaged corrective measures.

- The IE SA was unable to reach consensus, having considered the objections of the CSAs, and consequently indicated to the Board it would not follow the objections. Accordingly, the IE SA referred them to the EDPB for determination pursuant to Art. 65 (1) (a) GDPR, thereby initiating the dispute resolution procedure.

- Today, the EDPB adopted its binding decision. The decision addresses the merits of the objections found to be “relevant and reasoned” in line with the requirements of Art. 4 (24) GDPR. The EDPB will shortly notify its decision formally to the concerned supervisory authorities.

- The IE SA shall adopt its final decision, addressed to the controller, on the basis of the EDPB decision, without undue delay and at the latest one month after the EDPB has notified its decision. The EDPB will publish its decision on its website without undue delay after the IE SA has notified their national decision to the controller.

Coming to the present, in tandem with the publication of the DPC’s revised decision, the EDPB issued “Binding decision 1/2021 on the dispute arisen on the draft decision of the Irish Supervisory Authority regarding WhatsApp Ireland under Article 65(1)(a) GDPR” in which it assessed the DPC’s draft decision and the “relevant and reasoned objections” made by the DPC’s fellow DPAs. Generally speaking, the other regulators saw WhatsApp’s conduct as being far graver and deserving a more significant punishment. One criticized the DPC for not also investigating whether WhatsApp was sharing personal data with Facebook and whether this was being transferred out of the EU. The EDPB ended up in the middle on the appropriate punishment but often sided with the CSAs on the messaging app’s GDPR infringements. One could conclude the EDPB was not impressed with the DPC’s decisions after its investigation, particularly since the Board again and again came back to the investigator’s findings on WhatsApp.

The EDPB summarized its decision:

Not much needs to be said about the EDPB’s summary other than the fact that the German, French, Hungarian, Italian, Polish, and Dutch data protection authorities (DPA) objected to the DPC’s draft decision and punishment.

The EDPB summarized the objections of the DPAs to the DPC’s draft decision:

The EDPB explained the DPC tried to address some of these objections in a compromise draft, but “the responses received from the concerned supervisory authorities (CSA) in relation to the remaining objections showed that there was no single proposed compromise position that was agreeable to all of the relevant CSAs.” And so, the DPC could not please all the CSAs, and the matter was kicked over to the EDPB to decide, the second time a proposed DPC decision had to be decided there.

The EDPB states at the outset of its analysis of the CSAs’ objections that it will only analyze those that are “relevant and reasoned” (i.e., the threshold for the EDPB to intervene under the GDPR). Moreover, the Board does not take any position on those objections that are not relevant and reasoned for future potential action.

The first objection the EDPB examines is over the DPC’s analysis of whether WhatsApp was transparent enough in explaining to users its alleged legitimate interests in processing data per Article 13(1)(d) (i.e., the requirement that a controller must disclose to a person at the time personal data is collected the legitimate interests of the controller or third party is using under the GDPR). The EDPB found the objections the other CSAs raised to be relevant and reasoned despite the DPC’s arguments to the contrary, specifically the Board agreed that WhatsApp was not transparent enough in explaining its legitimate interests to people such that they could then have information sufficient to exercise their other rights. Accordingly, the EDPB agreed with the CSAs (and incidentally the DPC’s investigator) that WhatsApp’s disclosure about the purposes and legitimate interests in data processing were inadequate to the requirements of Article 13(1)(d) and ordered the DPC to revise its decision thusly.

The relevant portions of this analysis are:

As noted, the EDPB concluded:

Presumably, WhatsApp would be wise to consult the Article 29 Working Party’s guidance on transparency the EDPB ratified shortly after its establishment. In a footnote, the EDPB quoted from these guidelines in terms of what not to do that sounds close to how WhatsApp described their “legitimate interests” and the purposes for processing:

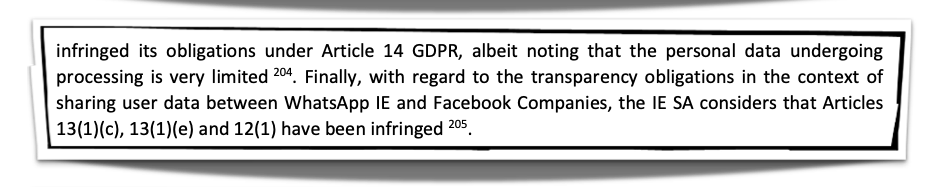

Next the EDPB turns to WhatsApp’s “Lossy Hashing” procedure that supposedly turns the phone numbers of a user’s contacts into a hash within seconds. This analysis implicates non-users of WhatsApp and a different but related article of the GDPR. The DPC initially found this processing did not pertain to personal data, and consequently, the company’s infringement of the GDPR’s Article 14 was not as seriously, meaning a significant reduction in the proposed fine. Again, CSAs sided with the DPC’s investigator in arguing the Lossy Hashing process did not change the fact that phone numbers are personal data despite the alleged transformation. Things get very technical hereafter, and I was struggling to follow the arguments of the CSAs as explained by the EDPB. However, the gist seems to be that the lossy hashing procedure does not lead to the anonymization of non-users personal data, at which point the GDPR does not apply. Rather the CSAs argued the process leads to pseudonymization, and that WhatsApp is able to easily reidentify users. Moreover, the 16 numbers associated with each lossy hashed non-user are likely the maximum number of numbers used and not the minimum. The DPC came around to some of the arguments, especially in light of establishing an untenable precedent, but worried about losing in court. The DPC tried splitting the baby in half by proposing:

The EDPB ultimately found all the objections raised to be relevant and reasoned and further explained:

On this point, the EDPB sided with the CSAs again:

Germany’s DPA leveled additional objections, including whether the DPC got the scope of the investigation right and whether the agency should have consulted with other DPAs in making this determination at the outset of the investigation. Clearly, the German DPA favored a wider-reaching investigation, especially into whether WhatsApp was sharing personal data with its corporate parent, Facebook. The DPC did not agree and referenced other, ongoing investigations into both WhatsApp and Facebook with the latter pertaining to international transfers. This is most likely a reference to the long-running litigation brought by privacy advocate Max Schrems that has resulted in two EU adequacy decisions regarding the U.S. being struck down. Earlier this year, Schrems and the DPC reached a settlement that could expedite the agency’s determination of whether Facebook must stop transferring personal data to the U.S. on the basis of the court decisions. In any event, the EDPB did not find the German DPA’s objections relevant and reasoned.

The EDPB did find the Italian DPA’s arguments on whether WhatsApp violated the transparency provisions in Article 5 to be relevant and reasoned. The EDPB found:

The EDPB agreed with CSAs that took issue with the DPC declining to find violations of Article 13(2)(e), which controls some of the information controllers must give to people at the point of data collection. In this case, this provision pertains to “whether the provision of personal data is a statutory or contractual requirement, or a requirement necessary to enter into a contract, as well as whether the data subject is obliged to provide the personal data and of the possible consequences of failure to provide such data.” The EDPB found this to be a relevant and reasoned objection:

On a different infringement the CSAs found under Article 5(1)(c), the EDPB stated the file of the case lacks the elements necessary to make this determination.

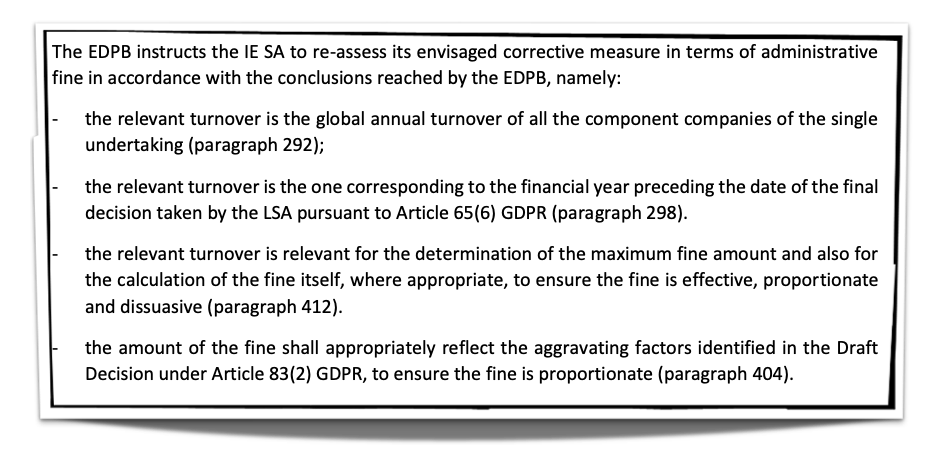

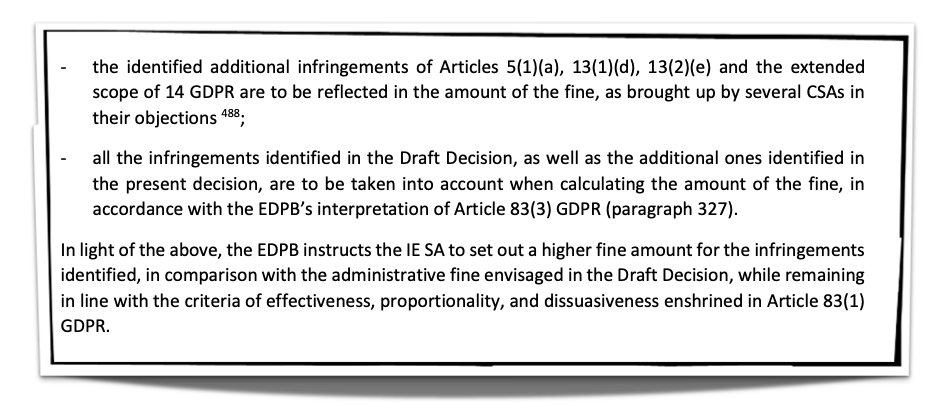

The EDPB analyzes at length how the DPC calculated the annual turnover rate for WhatsApp and Facebook, which serves as the basis for any administrative fine, and other facets of how to properly calculate fines. Ultimately, the EDPB reveals the DPC wanted to fine WhatsApp €30-50 million, to which the CSAs objected. For example, the German DPA advocated for a fine in the “upper range” closer to 4% of Facebook’s annual worldwide turnover (over $80 billion), suggesting a fine in the range of $2 billion or more considering in rough number $3.2 billion is 4%. The other DPAs lodged similar objections, arguing that a low fine does nothing to dissuade WhatsApp and other companies from future similar conduct. The EDPB found:

The EDPB directed the DPC to reassess the proposed fine:

One general point I didn’t make in the last post about the DPC’s decision that is also relevant to that article is how long it takes for some DPAs to move from investigation to a final decision. In the timeline here, the DPC started investigating WhatsApp in December 2018, and even if no other DPA had leveled relevant and reasoned objections to the draft decision, the matter would have been settled in December 2020 at the earliest. In those two years, it appears WhatsApp was free to continue collecting and processing personal data as it wished, for there was no sort of order or injunction blocking these activities. Perhaps this is a matter of resources, for in Brave’s 2020 report on DPAs, the browser company alleged that “the EU Member States have not given data protection authorities (DPAs) the tools they need to enforce the GDPR.” And the DPC has complained that its recent funding increases may be inadequate for its workload, which is significant because it is the LSA for Facebook, WhatsApp, Twitter, Apple, Microsoft, and others in the EU.

© Michael Kans, Michael Kans Blog and michaelkans.blog, 2019-2021. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Michael Kans, Michael Kans Blog, and michaelkans.blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Photo by ishan shah on Unsplash

Photo by Hugo Jehanne on Unsplash