Subscribe to my newsletter, The Wavelength, if you want the content on my blog delivered to your inbox four times a week before it’s posted here.

The Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee issued a sequel to a 2019 report on federal cybersecurity that examined eight agencies and found them lacking in a number of regards. However, the committee’s proposed fixes fall short of addressing the tenuous state of United States (U.S.) federal government.

In June 2019, the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee’s Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations (PSI) released a staff report on federal cybersecurity and found in the four years since the enactment of the “Federal Information Security Modernization Act of 2014” (FISMA), “federal agencies have failed to substantially improve their information security posture.” PSI further asserted that “[t]he vast majority of the federal government has failed to implement basic and effective data security controls—leaving PII and other sensitive information vulnerable to exploitation.” In making these determinations, PSI examined the annual Inspector General reports on FISMA for seven agencies “cited by OMB as having the lowest ratings with regard to cybersecurity practices based on NIST’s cybersecurity framework in fiscal year 2017.”

Perhaps it is not an accident that federal contractors who sell the federal government billions of dollars in ICT goods and services annually are not mentioned. For one, looking at contractor vulnerabilities and shortcomings runs counter to the usual focus of Republicans in federal cybersecurity and data security. They often prefer to keep the aim squarely on the agencies themselves while omitting the limitations agencies work under in procuring goods and services that can be favorable to large contractors. Moreover, this focus dovetails with the customary Republican narrative of government ineptitude and inability to compete with the more agile and nimble private sector that always outclasses departments and agencies.

Additionally, on this point about contractors and private sector entities, the committee describes in some detail the SolarWinds and Pulse Connect Secure breaches that allowed Russian and Chinese hackers to access the systems of many federal agencies. To be sure, U.S. agencies were penetrated unaware through these private sector offerings, and there is sufficient blame to go around the federal government. But the committee elides the fact these were private sector entities with whom federal agencies in a number of cases were contracting. A considerable weak point in federal systems are private sector contractors motivated by profit, meaning security sometimes gets short shrift. And so, it makes sense to pair measures to drive better cybersecurity among public sector entities with those designed to do the same among the private sector entities contracting with the U.S. government.

In a sense, there is not much that is new in this report. The committee is relying on OIG FISMA reports that are released annually, and it may be fair to assert the committee is just pulling the information together, which can often be a helpful task.

Nonetheless, the committee compared the most FISMA reports for the same agencies it had examined two years before and concluded:

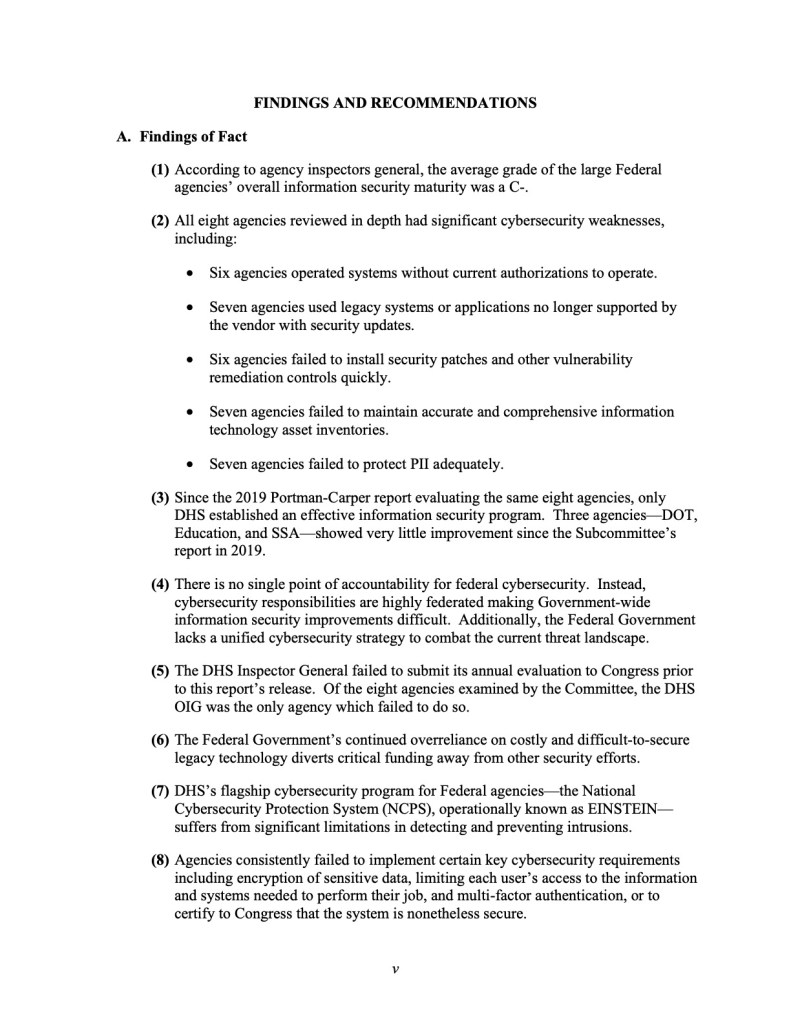

The committee identified a grim list of findings:

To reiterate a point made earlier, whatever role private sector entities play in U.S. federal cybersecurity, the agencies examined are failing to take some basic steps to help themselves such as encrypting sensitive data, access controls, or multi-factor authentication.

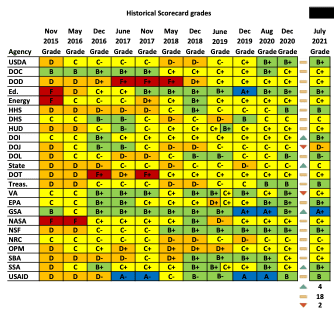

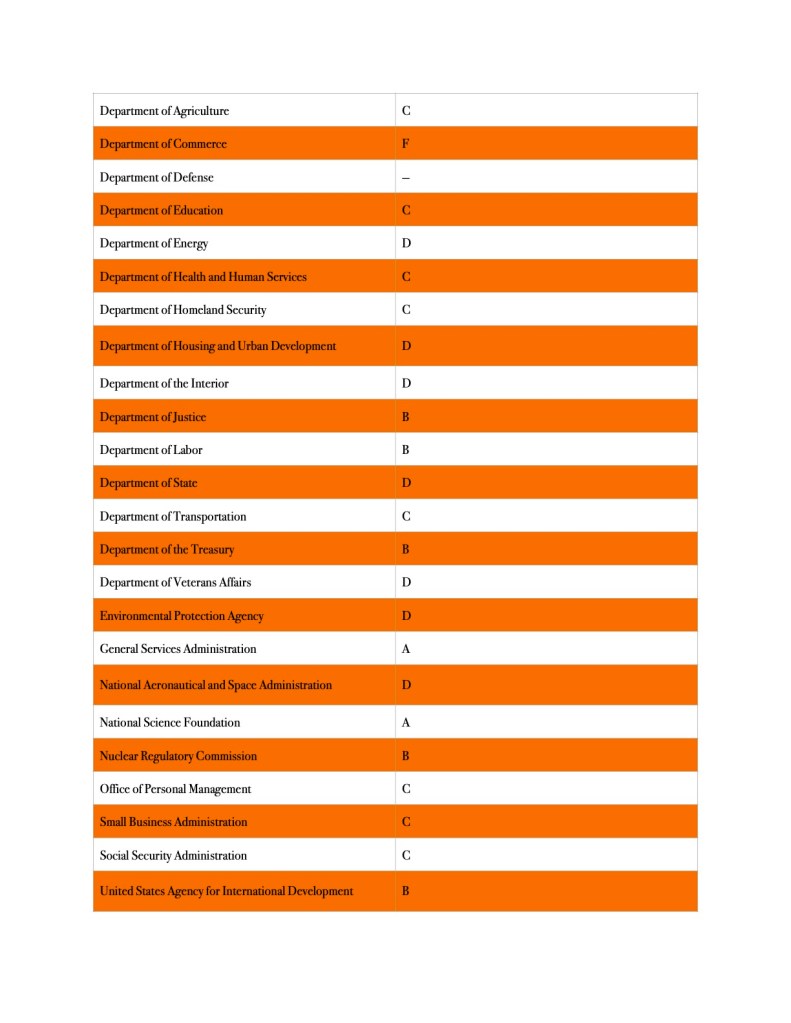

The committee also issued a report card based on agencies’ FISMA scores:

The House Oversight and Reform Committee issued recently the 12th Federal Information Technology Acquisition Reform Act (FITARA) (P.L. 113-291) scorecard gave some of these same agencies very different grades, admittedly according to criteria OIGs did not use:

The House Oversight and Reform Committee’s Government Operations Subcommittee and the Government Accountability Office (GAO) collaborate to compile FITARA scorecard. This is a different process using different metrics from the OIGs under FISMA use. Nonetheless, FISMA is a component of the FITARA scorecard and the grades given to the agencies do not match the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committees:

The committee made the following recommendations:

Some of the 2019 recommendations did not make the 2021 list. For example, two years ago the committee called on the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) to ensure that chief information officers (CIO) have the authority to make agency wide decisions on cybersecurity. The FITARA scorecard may explain why this is no longer a pressing issue, for most agencies now have their CIO in a position to directly report to the agency head, meaning the CIO is organizationally positioned to be more effective. This has long been seen as a way to drive better cybersecurity. A similar recommendation was made in 2019 regarding information security and CIOs reporting to agency heads. The FITARA scorecard also shows a number of agencies earning A’s in the category of enhancing agency CIO authority, and thus these two recommendations may not be as pressing as they once were.

In 2019, the committee urged OMB to conduct more CyberStat meetings with agencies. A 2019 GAO report found that these joint OMB and DHS meetings had dwindled in number since FY 2016. There has been no public indication OMB and DHS have reversed this trend, and yet the committee did not recommend that they be reinstated.

Of greatest interest is that the committee is calling for Congress to revisit and refresh FISMA, which was last revised in 2014. The committee asserts the statute should be revised thusly:

- To reflect current cybersecurity best practices, including focusing on mitigating identified and analyzed cybersecurity risks, in addition to meeting compliance risks;

- To formalize CISA’s role as the operational lead for federal cybersecurity;

- To require federal agencies and contractors notify CISA of certain cyber incidents; and

- To define “major incident” in a way that ensures federal agencies notify Congress in a timely manner of significant cyber incidents instead of continuing to rely on the current definition which has promoted inconsistent notification to Congress.

And yet, one wonders how well these legislative revisions would address the parade of horribles the committee found to persist after two years and its initial report. The heart of the recommendations seems to be enhanced reporting requirements for agencies and contractors and a standard definition of “major incident” so agencies cannot define away incidents they would prefer not to report. Also, DHS’s Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) would be deemed the federal operational lead on cybersecurity, leaving as an open question whether this would apply only to the civilian side of the government. It is unlikely the Department of Defense (DOD) and the Intelligence Community (IC) would give on the current, largely bifurcated system of oversight with DHS and the IC would give on this point without a fight. In all, these recommendations do not seem to address the problems the committee turned up.

To be fair, conceivably the executive branch and the White House already have the authority to effect some of these changes, but a statutory mandate may prove more efficacious. For example, Congress could enshrine in law a statutory responsibility for DHS to report on EINSTEIN budgeting and progress very year or every two years as a means of forcing the agency to focus time and energy on this system of protecting federal networks.

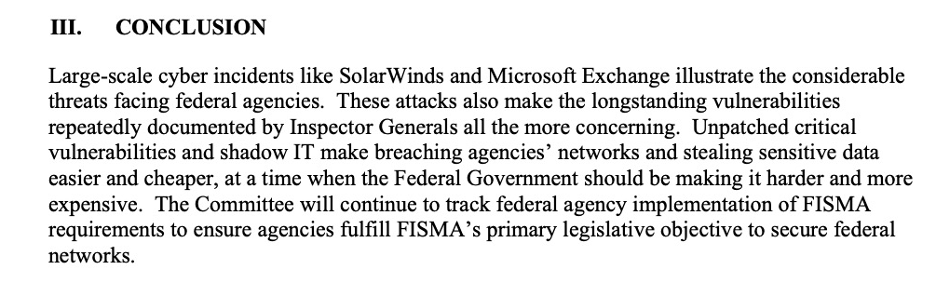

In any event, the committee concluded:

© Michael Kans, Michael Kans Blog and michaelkans.blog, 2019-2021. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Michael Kans, Michael Kans Blog, and michaelkans.blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Photo by Paul Gilmore on Unsplash

Photo by Denny Müller on Unsplash